Pace-O-Matic

Happy 25th Birthday, Pace-O-Matic

& Happy 50th Industry Anniversary, Michael Pace!

Pace-O-Matic, a leader in the skill gaming market, is celebrating its silver anniversary this year; its success is the culmination of its 25 years of hard work and innovation and the 50 years of industry experience, invention, and engineering uniquely belonging to the company founder, Michael Pace.

The company has grown nicely over the years, now employing nearly 200 people in 13 departments at its Duluth, Ga., headquarters (northeast of Atlanta). Today, their games can be found in markets, including Pennsylvania, Texas, Wyoming and the District of Columbia. Unlike game terminals you’ve seen in casinos where chance rules the day, with Pace-O-Matic’s games, the player wins by using strategy to solve puzzles within a limited amount of time. The company says it’s even possible for a skilled player to win every time.

Titles in their roster include Hi-Way 50’s Overhauled, Under the Mountain, Wildebeest Wild, Amigos Locos, Lady Periwinkle’s Curious Contraption, Living Large, Pirates and Gem Master and others. The games are fun, but more importantly, the company boasts that their revenues have a significant positive impact on small businesses and the communities in which the games are operated.

Michael and Karmin Pace with CEO Paul Goldean in the company’s headquarters in Duluth, Georgia, just a bit outside Atlanta.

A Little Backstory

RePlay first met Michael Pace while attending his Digital Controls distributor meeting in Atlanta, where he and then-partner Mike Macke were showing off their Little Casino countertop video game. It was 1981, and the duo had a winner. The machine didn’t take up much space on the bar top, and players loved the poker, blackjack, Hi-Lo and craps housed inside the compact powerhouse. It was designed for amusement only, said Pace, with location patrons playing for fun and points alone. Case closed.

Over the following decades, the public demonstrated its desire for gaming-style amusements outside the traditional casino setting, approving Indian gaming, state lotteries and skill games where it would be legal to win money. In the process, the skill game business has grown up and become more mainstream, due in no small part to the efforts of people like Michael Pace through design, lobbying and legal defense.

Make It Fun, But Keep It Legal

For Pace-O-Matic, ensuring their games are not only fun to play but legal and in full compliance is job #1, says Pace. His business model has been refined over the years to a winning formula: develop top-earning games that are both legal and defendable in that market.

“First, I have to design so it complies with the law and will be easy for a judge to understand that,” Pace said. Then, I make the games clear enough for the players to understand, or they’ll never play it. And finally, I’ll make it as fun as I can.”

When Pace was running U.S. Games, a company he founded after he left Digital Controls, he developed the Pot-O-Gold hardware platform that became the foundation for future game development. “Later, in 2002 when I was working in the Oklahoma market, I used money made from the software upgrades to build the next-generation board set. It was also the start of what I call the “fill system,” which I refined for the Ohio market.

Fill was short for “refill” and referred to how operators would be sold a code to reload their pull tab machines. The cost of that code went to support defending any games should there be questions regarding their legality.

“Basically, what they were paying for when they bought the code was a bit of an insurance policy, that I would be there to provide a unified defense should a game get picked up,” Pace explained. “It shouldn’t have happened because the games were legal, but when it did, I would go to court as an expert witness and prove the legality of the machine.”

Today, Pace-O-Matic still uses the term “fill,” but in a different way, Pace explained. “Our fill system ensures operators are compliant with the law. This has helped solve the problem of legitimizing the skill game industry. This ‘fill system’ has revolutionized everything. It makes it better for everyone.” Problem solved.

Today, Pace-O-Matic still uses the term “fill,” but in a different way, Pace explained. “Our fill system ensures operators are compliant with the law. This has helped solve the problem of legitimizing the skill game industry. This ‘fill system’ has revolutionized everything. It makes it better for everyone.” Problem solved.

The system also takes care of paying the states their share. “For example, we’re highly regulated in Wyoming,” he explained, “and instead of the state having to collect from the operator, we automatically get the information from the fill system and pay the state their percentage directly. Now, the state doesn’t need compliance people or an entire regulatory division, which saves them money.”

Helping with these accounting and reporting tasks is their Velocity system. In 2020, Pace-O-Matic bought MCM Elements, a well-known route accounting software company that had a suite of tools covering the operation of games, ATMs and other on-the-route equipment.

Rebranded Velocity after the acquisition, the data collection system “knows exactly what’s going on with every machine down to the penny and electronically filling the games,” Pace said. Velocity continues to offer its integrated route management tools, which consists of RouteBoost, CashKeeper, TicketShield and RouteBoostPro.

In most markets, Pace-O-Matic leases both the software and game cabinets to the operator. “By maintaining ownership of the cabinets, we can make sure someone’s not out there switching out our legal boards for something else.” (Things like that can happen. For example, they won a case in federal court after some people in Pennsylvania put the Pace-O-Matic logo on a game, but it wasn’t the company’s software inside, it was an 8-liner. Pace said, “It looked to the cops like it was our product but it sure wasn’t!”)

Future Growth

While other ideas have come along, like researching how players could play using their phones during Covid, Pace says they know their lane and stay in it.

“We stick with this core market of operating games in bars and restaurants because we’re really good at it. And we know all the operators, or at least most of them. We pride ourselves on partnering with operators who are professional, straight up and will do it right.”

Mary Jo Bishop and her husband Paul, owners of Steggie’s Bar (Lebanon, Pa.) with a Pennsylvania Skill game.

Silver Anniversary

“When we’re talking about the legacy of Pace-O-Matic, one thing the company prides itself on is that we’ve created a product that locations can use to make supplemental income at no risk and in a small footprint,” said Rachel Albritton, VP of communications for Pace-O-Matic. “Our products have not only revolutionized the amusement business, which has had its own challenges, but also retail establishments, bars, restaurants, VFW halls and American Legion posts where you can find skill games. Our innovation in the industry met a need that existed.

“The change in consumer habits, like using third party platforms like Uber Eats, makes it challenging sometimes for locations to bring people into the restaurant or bring people into the store,” she added. “The question is how to get people back into the brick-and-mortar establishments. For example, we have grocery store locations, and the skill games can help with getting people to come in to play, and then they’ll buy more products. In a restaurant, they might get an extra appetizer while playing.”

Michael Pace was especially proud of how they’ve helped keep mom and pop shops in business. And as they proclaim on their website: “We support small businesses, the very fabric of America.”

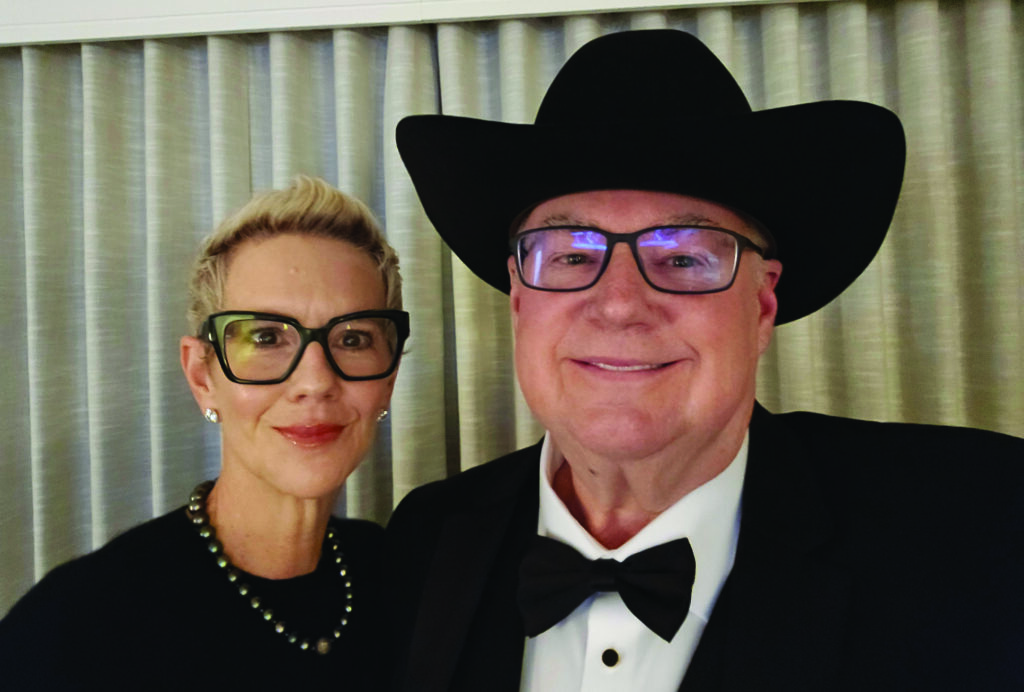

A perfect pairing – Michael and Karmin Pace, who celebrated their 25th wedding anniversary last year, have homes in Montana, Tennessee and a lake house in Georgia. Of his wife, he said, “She’s just my dream come true. We really are partners, and it works so well. She does her part, I do mine and we make more than we need. That’s a good thing that allows us to involve ourselves in philanthropy in a big way.”

Fast-Paced

The Michael Pace Story (or at Least a Portion of It)

It might not be completely accurate to say that Pace-O-Matic founder Michael Pace – an inventor, engineer, pioneer and entrepreneur – pushed himself to learn new things and problem-solve constantly; it’s probably better to say it’s in his DNA.

Born in 1957, he caught the electronics bug early in life from his father, building Radio Shack and Heathkit projects in the 1960s. In grammar school, Pace would come home from school and spend hours paging through the volumes of the Encyclopedia Britannica and World Book, stopping to read more closely when he found things of interest.

“I could spend hours, and it was so fascinating to me. I spent probably two to three years doing that. In the process, I found that if I really want to know something, all I have to do is read it twice. The first time, I’ve basically got it, but by the second read, I start to project what the next sentence is going to be.”

By the time Michael was 12, he understood semiconductor theory. A traveling salesman selling correspondence courses in electronics stopped by the Pace house when Michael was in 9th grade and he jumped at the chance to learn, taking the FCC license course.

“It took me about two years to do all that, but I learned a hell of a lot! Even today, I still can design and build RF transmitters with vacuum tubes,” he said of what’s become a lost art in electronics.

When he was in 10th grade, he developed an electronic laser scanner and then created an original laser light show for an event in Stone Mountain, Ga. (A friend had a show booked there and when his engineer quit, asked if Michael could help. After doing so, Pace went on to do other shows for bands, amusement parks, etc.) He helped build a recording studio in 1978 and became very skilled with audio engineering.

“Later that year, I built the world’s first telephone soliciting machines out of a kit computer. In those days, I built my own computers on breadboards, plastic boards used in prototyping electronics projects. Anyway, this thing would call people on the phone, give them pre-recorded questions, and record their answers. These were those calls that irritate everyone,” he laughed.

As bright and eager a learner as he was, it wasn’t the typical school studies that could hold his attention. Not only was the pace too slow, but the material just couldn’t hold his attention. He discovered this while paging through the encyclopedias years earlier … history and other topics didn’t hold a candle to science, math and technical content.

“For example, if I try to read fiction, I can maybe get to page three before my brain is way off on something else. Often, I’m at the dinner table having a conversation with someone, but my mind is going 900 miles an hour on something I’m trying to solve. I can’t change that… that’s just built in, so I try to use it to my advantage. And this was the way I was when I was young, too. I found that scientific stuff kept my brain focused because it was more difficult and required me to think more. I could follow it much more easily than reading a textbook or fiction.

“And that is what really got me into science, technology and mathematics,” he continued. “They entertain, or focus, my brain. I still have a terrible attention span, but that’s what makes me creative. So, if you try to fix that, I can’t invent things. I never understood why people play sports, and I thought, why would you play somebody else’s game when you can invent your own? I know that sounds crazy, but that’s how I was.”

And that’s what he did, starting in 1975 when he used his school’s IBM 370 mainframe computer to program his first games. “I wasn’t going to school, I was playing on the computers. So that’s where it really started and, even though I was fixing pinball machines four years earlier, when I first started programming games is what I consider to be ‘day one’ of my career.”

In 1978, he started Pace Age Technology, a play on “space age,” and got into repairing Ohio Scientific computers, one of the first business computers on the market. “I was the only person in the Southeast who could fix them.” Needing to travel around, he learned how to fly and by 1979 was renting airplanes and then “I ended up buying a few,” he said.

Using an early Apple IIe computer, he developed a system to help companies save money on their power bills during the energy crisis by digitally controlling HVAC systems and called the company Digital Controls. In addition to the energy management systems, Pace was doing some other projects on the side and met a man, Greg McManus who told him, “I don’t know what you’re going to do in your life, but I want to be a part of it,” bankrolling Michael with a $100,000 investment.

When the energy crisis was over and the market for the control system dried up, he had about $15,000 left of the seed money and focused his attention on one of the other projects he’d been working on: a game he had developed and built in his bedroom.

“I told Greg that I was going to get into the games business, and that this stuff was going to work, but that I was going to be spending 80 hours a week engineering the project. We’d need help running the business and handling sales because I wouldn’t have the time.” McManus suggested a Cobol language programmer he had working in his trucking company, Mike Macke, who would become the third partner in the countertop game company.

A trip in RePlay’s Way-Back Machine transports us back to the early 1980s when two youngsters, Michael Pace (right) and Mike Macke (now known for his Primero Games) were running Digital Controls and making countertop video game history with the Little Casino.

Their product? The innovative Little Casino.

“This was in 1981, and these games took off. Within six months, we were doing something like a million dollars a month in sales. Little Casino was the first countertop video game that played poker, blackjack and craps. It was small and fit easily on the bar top. Adults loved to play even though they didn’t pay off – you only played for points,” he said, adding, “Honestly, I was scared to get into the credit poker business!”

Still, he said those early games took in about $400 a week, all in quarters. “I engineered this large cash box, because there weren’t bill acceptors back then. The first Little Casinos were also just black and white – I bought these little black and white TVs and modified them to work, designing a board for the NTSC signal. Later, with Little Casino II we had 16 colors. People loved them and they made a lot of money for operators and locations.”

In 1984, Macke and Pace also bought a company called the Learning Center, which was trying to put together laserdisc-based computer education (like how to use Lotus 1-2-3 or a PC). “I modified one of my Little Casinos so it would run a laserdisc player and designed an all-new, high-resolution board. We also turned the screen 90 degrees. No one had done that before. Because we were involved with that company and technology, we went on to design Cowboy Casino.” Introduced in 1984, Pace said it was the first countertop laserdisc-based interactive coin-op game. (The game came on the market about the same time as Sega’s Astron Belt and Cinematronics’ Dragon’s Lair laserdisc games.)

Financially, Digital Controls was going to need to sell off the Learning Center to recoup their investment and get back to doing what they did best, and in 1985, they were close to sealing the deal with IBM when tragedy struck. In August of that year, every member of the IBM group working on the project, including the inventor of the IBM PC, perished in the crash of a Delta L-1011 in Dallas.

Digital Controls wound down in mid-1986 with Macke and Pace going off to do their own projects. By September, Pace incorporated his new company, U.S. Games, designing a new, full-color, character-based video control board, which was the core of their new game, Super Duper Casino. But by then, competition in the countertop market had really heated up, and sales of the Super Duper Casino units were cooling. At the same time, Pace had decided to build games for the South Dakota lottery. He knew he needed a high-resolution board and dubbed it Pot-O-Gold and even though they entered the South Dakota market a bit too late, finding it already saturated, Pot-O-Gold was indeed golden!

The Pot-O-Gold hardware platform, introduced in 1990, was used to develop games using the same name for the Tampa, Fla., Seminole tribe, then the Cherokee tribe in North Carolina and other Tribal Nations. Pace secured gaming licenses in Minnesota, Wisconsin, New York, North Carolina, Mississippi and Montana. In complying with Class 2 Indian Gaming regulations, Pace used his Pot-O-Gold board to invent the first electronic pull-tab dispenser and the first integrated progressive.

“This was a real game changer. With the reliable technology, you could finally store changing values that were in the hundreds of thousands of dollars and not have to worry about the board glitching that would mess it up. It was that reliable of a memory circuit. Up until that time, no one had the ability to store electronic data very reliably.”

In 1996, Pace sold U.S. Games and, having fallen in love with the American West while on a road trip when he was 21, retired and bought a ranch in Colorado, later buying one in Wyoming. He loved that life (he still has a place in Montana) but came out of retirement in 2000, founding Pace-O-Matic, and applying everything he’d learned to the skill gaming industry.

These days, Pace is plenty busy but tries hard to step back and let his talented programming and engineering teams do the heavy lifting. In addition to other company matters, Michael and his wife Karmin focus on their numerous philanthropic efforts.

He and his wife bought a home on the Tennessee River in Chattanooga, Tenn., in 2024 and noticed developers creating large-scale housing communities along the escarpments of the Cumberland Plateau. The relatively inexpensive land, rising some 1,400 feet, is surrounded by nature and offers incredible views. Michael and Karmin immediately wanted to preserve that beauty.

“We found a piece of land there on top of the plateau that also went down to the bottom and back up the other side. And there were a bunch of other parcels. So, over a year, we bought 10,500 acres along the Little Sequatchie River and set up a 501c3 called the Appalachian Conservation Institute. We hired a former federal game warden to run it and have a total of eight people who manage it. While it’s not public, per se – we have no problem with people enjoying the land – we just want to know who’s on it at any given time.

“It’s unbelievable. We have eight miles of river, 10 miles of cliffs, waterfalls and 77 known cave systems down on the river. While the land has trees, it has been logged heavily on top and we’re letting it grow back and be natural.” The institute has also implemented a bird-banding program and, through monitoring their patterns and populations, hope to better understand their environmental changes and inform their land management.

Michael Pace also has a new project near and dear to his heart that readers will hear more about in the coming months. Called the Integrity Award, Pace wants to honor people of character in the industry, often the unsung heroes of the industry. “I’ve been working on this idea for two years. We want to give them to people in the industry who are honest and have done the hard work but, for whatever reason, haven’t gotten the recognition they deserve.”