What a Strong Collection!

Museum of Play Offers Wonderful Ode to Coin-Op

by Matt Harding

Jeremy Saucier, the Strong National Museum of Play’s assistant vice president for interpretation and electronic games.

The Strong National Museum of Play in Rochester, N.Y., is a treasure trove of toys, dolls, action figures and games of all kinds. The growing facility owns and cares for the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts, materials and documentation related to all types of “play,” said Jeremy Saucier, the museum’s assistant vice president for interpretation and electronic games.

“We have more than half a million playthings,” he said. “While we have all these exhibits for people to learn and interact with and play in, we are a collection-based museum with a long history of collecting, too.”

The museum was initially created in 1968 as the Margaret Woodbury Strong Museum of Fascination, named after the founder, a wealthy Rochester resident whose family were early investors in the Eastman Kodak Company. Strong was a prolific collector of toys, dolls and dollhouses. Though she died only a year later, her collections and financial resources lived on, and in 1982, a physical museum took shape.

By 2003, the museum’s mission broadened to “collecting, preserving and sharing the importance of play.” Today, after three physical expansions, the 375,000-sq.-ft. museum is one of the largest history museums in the country, Saucier noted.

In the mid-to-late 2000s, the museum added the International Center for the History of Electronic Games. “We knew fairly early on that if we were going to collect and be an authority on play and its history, we were missing a lot,” he explained.

“When we moved to our ‘play’ mission, we quickly realized we didn’t have everything. Margaret passed away before video games and developments in the coin-operated game industry and had very few coin-op games in her collection.”

So, as time went on, the Strong Museum started adding to its collection of historic coin-op games and now has more than 400 in its collection. They don’t only have vintage games, but modern ones as well.

The Infinity Arcade has vintage games like these but also more modern ones including fan favorites from the Golden Age of video games like Defender, Joust and Frogger.

Last October, they opened an exhibit called Infinity Arcade that puts a lot of those games on display – rather, on play display – available for visitors to actually play.

It offers guests a history of arcade games themselves and also the arcade as a physical space. Dozens of games from the Golden Age like Defender, Frogger and Joust are in the Infinity Arcade, as are more recent titles like Raw Thrills’ NBA Superstars and Step Revolution’s StepManiaX rhythm game.

The permanent Pinball Playfields exhibit features games spanning 80 years of the classic game from the likes of Whiffle (1931) and Humpty Dumpty (1947) to more recent titles.

Another permanent exhibit is called Pinball Playfields, which as you could surmise, features more than 80 years of pinball history (once again, playable pinball history). There are pioneering machines like Whiffle (1931) and Humpty Dumpty (1947), and there are classics like Fireball (1972). There are also plenty of modern games from Stern Pinball.

You can also see rare artifacts, including playfield prototypes and sketches by legendary designers like Harry Williams, Mark Ritchie and George Gomez. It’s all about telling the story about how pinball play has evolved over the years.

The museum is also home to the World Video Game Hall of Fame (a recent inductee was Asteroids). Inductions are in May; the museum sorts through thousands of nominations each year. (Visit www.museumofplay.org to make a nomination.) A group of finalists goes to a selection advisory committee, plus there’s also a player’s choice vote so the public can participate.

Additionally, the museum features the National Toy Hall of Fame (Barbie and Monopoly were among the inaugural inductees); the National Archives of Game Show History; and the expansive Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play.

While the dedicated coin-op exhibits feature the most coin-op games, there are 70-80 on display in total across the museum. The American Comic Book Heroes exhibit, for example, features coin-op games within that theme.

The 20-ft.-tall World’s Largest Donkey Kong, created with Nintendo.

All told, following the museum expansion in 2023, there’s about 25,000 sq. ft. of museum space dedicated to the history of electronic games. Taking up the most space, perhaps, is the 20-ft. tall World’s Largest Donkey Kong, created with Nintendo (see the photo above).

“The museum collects these games and people can play many of them on display, but we also have a collection of materials that we use for display and that are in our library and archives – materials available to researchers,” Saucier reported. “We have materials from the likes of Atari and Williams/Bally-Midway, including original playfield sketches from the ’40s.” Key industry icons like Ralph Coppola, Ken Fedesna, Millie McCarthy and Carol Kantor are also represented in the museum.

And, not to toot our own horn, but RePlay back issues are a part of the collection as well. “RePlay is a resource that many researchers come from around the world to go through,” Saucier said. “Magazines and journals dating back to the 1920s really help them to understand the history of the industry.” (Fun fact: Jersey Jack Guarnieri donated his collection of RePlays, dating back to the first issue in October 1975.)

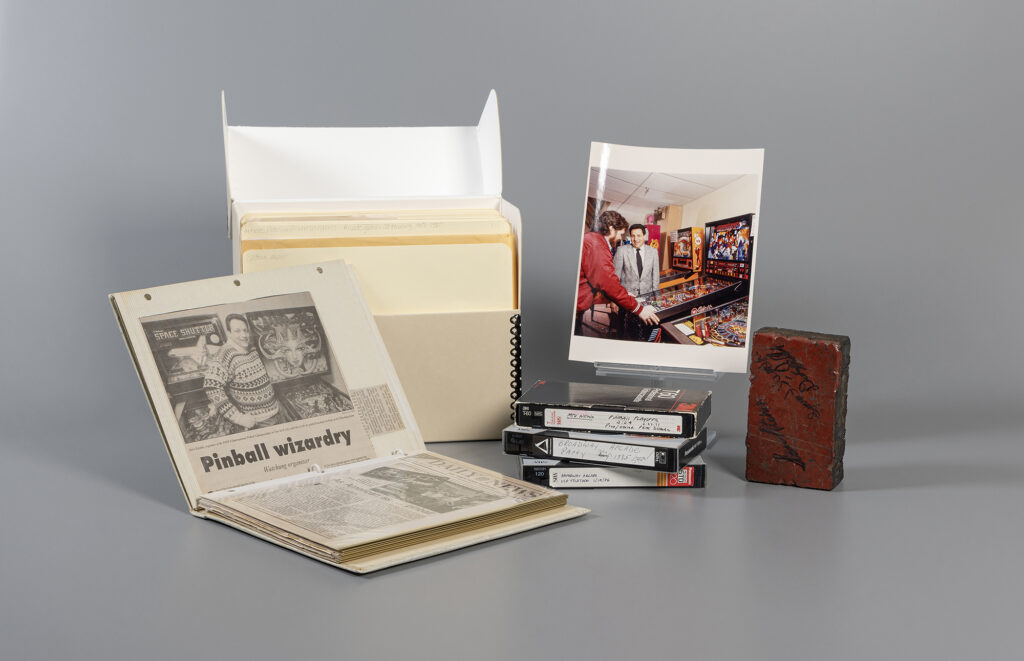

Recent donations to the museum are materials from the late Steve Epstein, owner of the Broadway Arcade in New York, that includes photos, videos and news clippings pictured above.

One of the most recent donations was from the estate of the late Steve Epstein, who owned New York’s Broadway Arcade. Those materials included photographs, videos, correspondence, newspaper clippings and much more – some of which are currently on display in the Infinity Arcade. “All of our exhibits are balancing interactivity with the background and the history of these materials,” he added. It’s ultimately about the play spaces, but it’s also a place to learn more about the games and overall industry history.

While most of the collection is available physically at the museum, there is a growing online database as well. “We hope to make more things available online in the coming years. When we can do it, we will, but collecting and preserving remains the top priority.”

Saucier has been with The Strong since 2012 and is also editor of their American Journal of Play. A former professor with a PhD in history, he’s become the de facto curator of the museum’s coin-op collection.

“Coin-op games in particular were really important for me,” he said. “I spent a lot of time at pizza shops and candlepin bowling alleys and local arcades. Video games were most accessible to me one quarter at a time.”

Now, he’s telling their story one cabinet at a time – and linking their overarching history to the beginning of “play.” The museum connects modern shooter arcades to kids across eras playing cops and robbers in the backyard with sticks and toy guns. Before pinball, there was marbles.

If you’d like to learn more about this fascinating history museum, or want to donate time or money, visit www.museumofplay.org.